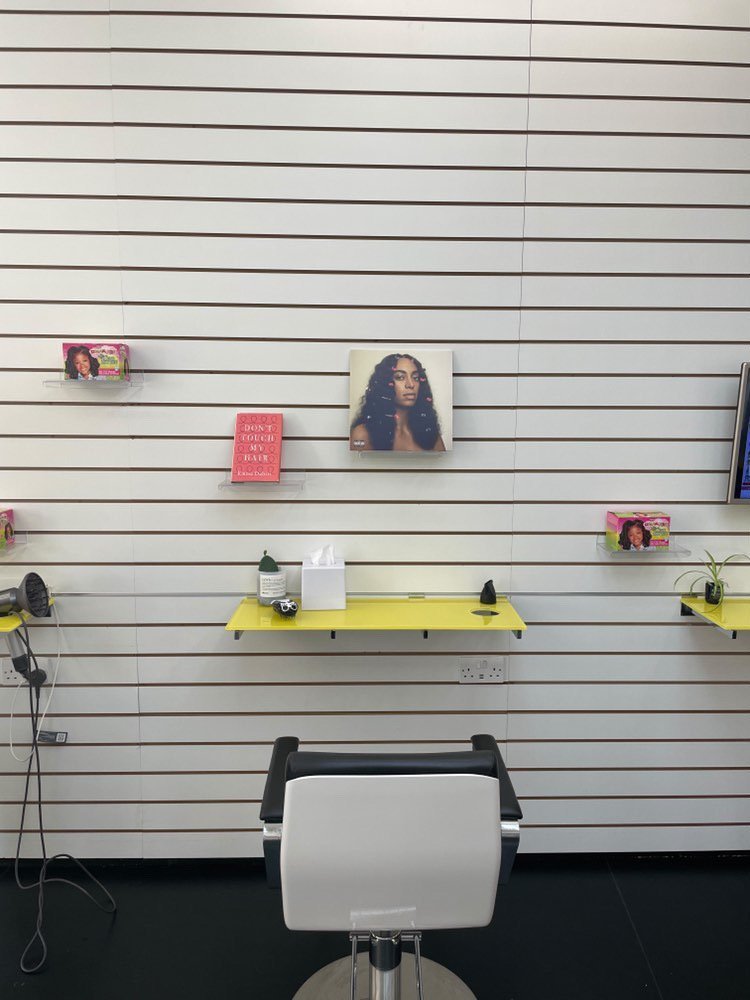

The salon reminds me that we are worthy of attention and the intimacy of examination.

At Brixton Tube Station in November 2021, Art on the Underground launched the artwork ‘5 more minutes,’ a large-scale painting by artist Joy Labinjo. Writer Jendella Benson responds to the artwork and asks readers to tap into communal, ancestral memory for just a moment, prioritising care and community over capitalism.

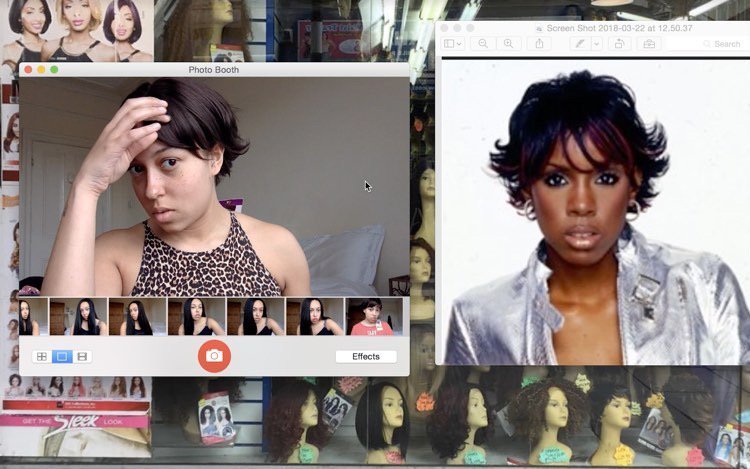

When I was a child, freedom looked like a Destiny’s Child video. While Beyoncé’s meticulously lined cat eyes and Kelly’s perfectly glossed lips were something to aspire towards, really, it was their hair that suggested a woman I wanted to grow up to become. LeToya’s feathered and highlighted brown hair; LaTavia’s thick corkscrew curls in deep, vibrant reds; Kelly’s purple pixie cut; all suggested a life filled with beauty and the money and time required to keep your hair looking that good.

Madelynn Green ‘Special Offer,’ 2021. ©- Courtesy of The Artist and Almine Rech Gallery - Photo: Melissa Castro Duarte

These were hairstyles that could not be achieved at home – believe me, even at that young age I had tried. I convinced my mother to partially relax (aka texturise) my hair in order to achieve the looser, springy curls of Spice Girl Mel B. But my hair briefly turned into lank, sad-looking clumps, before reverting with full force to its kinkier default after one wash.

Finally, when I was 11 years old, my mum took me to a real hairdresser. It was the kind I had seen in Destiny’s Child’s ‘Bills, Bills, Bills’ video, with overhead hairdryers, rows of gossiping, glamourous black women, and the artificial smell of flowers and fruit mixing with the heat of the pressing tongs.

As I took my seat on that black, pleather throne, my mother checked that I was alright before leaving to run errands along the high street. The adult conversation bubbled above my head while I stared hard at the mirror in front of me, watching the quick brown fingers of the hairdresser move through my hair, separating, combing and massaging me into the child I wanted to be.

While the supply chain for the tools of the trade is still controlled by mostly men of other races, the black hair salon is where our reign is unquestioned.

I left that salon looking and feeling like the smug little black girl on the front of the kiddie hair relaxer box. My ‘unruly’ coils had been tamed by a black iron tong into a sleek ponytail with a swooping fringe tucked delicately behind one ear. I looked like the R&B singers I idolised, my hair almost as blue-black as Michelle William’s thick, pressed waterfall in the music video for ‘Jumpin’ Jumpin’’.

In a world where beauty is currency, hair salons are sites of transformation, but not just for the clients who walk out with chins lifted. Hairdressers can weave gold for themselves and their families, the constraints of formal education, immigration status and other systematic barriers rendered useless, as long as you can turn the dream contained in a screenshot on a phone into a real-life crown. A hairdresser that can achieve that magic will be booked up month, after month, after month, an endless queue of women willingly pressing crisp pound notes into that soft, lined palm.

The hair salon is also the one place where motherhood, while still occasionally inconvenient, is not the mountainous hurdle it is in other professions. The exorbitant cost of childcare is averted as babies cling to backs or sit on clients’ laps. We may joke or complain how annoying it is when our braider stops midway to collect her kids from school, returning with children sure to make a nuisance of themselves, but on some level we understand. Better them here, bored and complaining or glued to smartphone screens, but still under the communal gaze of the shop, than elsewhere. A place can never truly be a safe space for a black woman if it is not also one for her children.

Black Hair Shop Zine, edited by Korantema Anymadu.

While the supply chain for the tools of the trade is still controlled by mostly men of other races, the black hair salon is where our reign is unquestioned. As gentrification erodes and decimates decades-old communities, it will be one of the last totems standing. This is one castle that the sweeping beam of colonisation will always struggle to fully penetrate. We are fortified by our own, sometimes problematic, beauty standards and languages of care that we recognise, first experienced as children clamped between the solid thighs of a mother or auntie.

To enter a black hair salon is to enter another world, where previous orders are upended. Black women wax lyrical on national politics, celebrity shenanigans or local news, their voices as authoritative and sharp as the decisive lines they draw with rat tail combs through oiled and stretched hair. Personal stories spill forth in Patois, Twi and Yoruba often speckled with Black British colloquialisms – “ya get me?”, “innit?” – and where words or advice fail, a knowing “mmhmm” or a derisive kiss of the teeth administered at the appropriate moment works just as well.

The community of women found in a hair salon is a breathing organism, expanding to embrace those who have travelled an hour or more to this particular spot to get their hair done just right. Those happy to accompany a friend to their appointment are welcome too, to flick through magazines or scroll Instagram as they eavesdrop and interject their own opinions. The lively, free-flowing conversation draws us all in, from the shy girl getting her cornrows in the corner, to the woman passing by, whatever pre-planned trip waylaid for “five minutes” or more.

For however long you sit within those storied walls, time is elastic and becomes a suggestion rather than a hard boundary. “Five more minutes” could mean 15, 20, 30 minutes or more, Depending on how full the salon is and what sort of chemical you have in your hair. “What’s the point in booking an appointment if I still have to wait?” many a client has asked with varying levels of attitude. In Don’t Touch My Hair, academic and broadcaster Emma Dabiri write about the politics of time and capitalism, and how white supremacy conquered and packaged our hours into productive units ripe for someone else’s direction or consumption. This thinking distorts how we view time, and what we consider a worthy use of it. Let us tap into communal, ancestral memory for just a moment, when our days were ordered not by the profit margins of an industrialised, cannibalistic system, but by the rhythms of nature, the needs of the individual and their community.

Joy Labinjo ‘5 more minutes,’ 2021 Commissioned by Art on the Underground for Brixton Underground station. Courtesy the artist and Tiwani Contemporary

“I remain curious as to what exactly it is that we are expected to be doing with our time?” Emma writes. “What is more profound or simply enjoyable than this type of activity? What is life for, if not physical intimacy and communion with our bredrin? If at the end of the exchange, we look better than we did before, issa win.”

“Nobody paid us any good attention, so we paid very good attention to ourselves,” Toni Morrison writes in The Bluest Eye, and the salon reminds me that we are worthy of this attention, the intimacy of examination. Fingers dipped in hair product tracing the coastline of your hair: “You have a little patch here. Maybe a bit of traction alopecia. Just be careful with it, yeah? I’ll braid around it, it’ll grow back.” The gentle inquisition as you get to know a new hairdresser: “So, you grew up around here? That’s nice. My aunt lived three streets over but she moved a long time now.” Your histories are exchanged in anecdotes, one memory at a time as the minutes blur into hours and in the mirror, you see yourself begin to take shape. Both of you and your hairdresser are bound together by this common purpose, like the two-strand twists slipping between her fingers like silk.

“Nobody paid us any good attention, so we paid very good attention to ourselves,” Toni Morrison