Kimathi Donkor, Mastering a Painting Practice that Comes Directly From the Heart.

In collaboration with Kensington and Chelsea Art Week, whom Black Blossoms have been working alongside since 2020 to champion Black visual artistic excellence in the UK, we present ‘On Episode Seven’ by Kimathi Donkor, which will intermittently appear on the Holland Park Billboard throughout 2023, we would like to thank Haleem Kherallah and Maximus for kindly donating the space.

Kimathi Donkor was born in Bournemouth, England and is of Ghanaian, Anglo-Jewish and Jamaican family heritage, and as a child, they lived in rural Zambia and the English Westcountry. He lives and works in London, where he is the Reader of Contemporary Painting and Black Art at the University of the Arts, London. Prominent exhibitions include War Inna Babylon at the ICA, London 2021, the Diaspora Pavilion (57th Venice Biennale, 2017) and the 29th São Paulo Biennial (Brazil, 2010).

His art re-imagines mythic, historical and everyday encounters across Africa and its global Diasporas, principally in painting and drawing; he sat down with Bolanle Tajudeen, founder of Black Blossoms, to discuss the artwork exhibited and his practice.

Dr Kimathi Donkor. Photo by David Poultney / UAL

Bolanle Tajudeen: Thank you for agreeing to have ‘On Episode Seven’ exhibited at the junction at Holland Park Roundabout; what was it like seeing the artwork there for the first time?

Kimathi Donkor: It was amazing. I came on my motorbike, so I first saw it when I was going around the roundabout and instantly, I thought, that is a spot! The work is poster-size on a large building, I don't think I've ever seen one of my works at that scale before, so it was a wow moment.

BT: I was driving around the roundabout when I first saw it and too and I screamed in excitement; it brightened up the skyline on a gloomy day. I felt intense joy when looking up at the painting.

Kimathi Donkor in front of his painting ‘On Episode Seven’ at Holland Park Roundabout.

KM: I intended to be a happy image; it feels happy.

BT: You recently took part in The World Reimagined, a national project seeking to address how the Transatlantic Slave Trade is understood; I loved your globe; why do you believe displaying art in public spaces is essential for society?

KM: Exhibiting publicly is increasingly becoming part of my practice; in the last two years, I have had more shows outside the gallery space. I had an exhibition at University College Hospital in London and a DKUK, a hairdresser in Queens Road Peckham, that was interesting because instead of having mirrors in front of a client, there is artwork. At first, I thought, is this what it has come to, a hairdresser? But when I looked into the space, I realised it was a great concept, a serious curatorial endeavour, and they had exhibited several well-respected artists. However, what was interesting was the idea of having a captive audience, which is quite unusual in the fine art world setting unless you are an artist working in film but for painters is relatively uncommon for audiences to have that extended encounter with your work.

Another public space I have been involved with recently is Tate Library on Windrush Square in Brixton, where community members come to read, work, and use it for meetings and events, so it was great to have my exhibited in such a multifunctional space.

So yes, in the last couple of years, there has been a genuine interest by people working in public spaces to show my work. I've embraced and enjoyed it as I share my practice with a wider audience.

BT: When curating art for outdoor and non-traditional spaces, I am thinking about the legacy of the GLC anti-racist Mural Project, which happened in the late 80s; I am also thinking about discourses surrounding the decolonisation of the arts. Do any ideas around decoloniality play a part in your decision to exhibit work publicly?

KM: Public art is ancient, going back 1000s of years. And each generation of artists goes through different phases of their work being more or less available to the general public. I come from a specific type of artistic production, which is very much related to galleries and museums. One could say that it is not necessarily decolonising but the opposite, a kind of colonisation. Art is reaching out from the gallery and museum space into wider sections of the general public. For example, in the Holland Park Roundabout space, the billboard is usually devoted to purely commercial needs, the selling of consumer goods. Whereas the idea of artwork is really about expressing a particular idea. There is a hunger and demand from the public to see communication, ideas, creativity, and beauty in the public realm, which is not just about commerce.

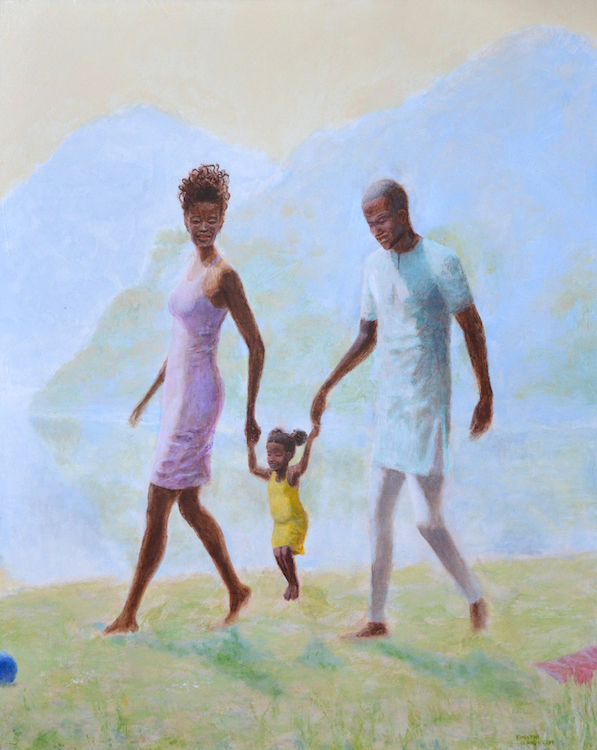

BT: I like what you said about the need to have beauty and ideas in the public space that isn't trying to grab our attention to sell something; art does this as it gives the viewer a moment to pause and reflect. The artwork, 'On Episode Seven,' definitely does this to me; I see myself, friends and family within the work and find it very cathartic to look at.

Is there anything socially or politically that has motivated this artwork?

KM: The painting is a part of a series called 'Idyll', and this poetic place is a place of beauty, repose, calm and serenity. An idyll is a place like that and is usually associated with an outdoor pastoral space, happy people and happy animals. Idyllic comes from the word idyll.

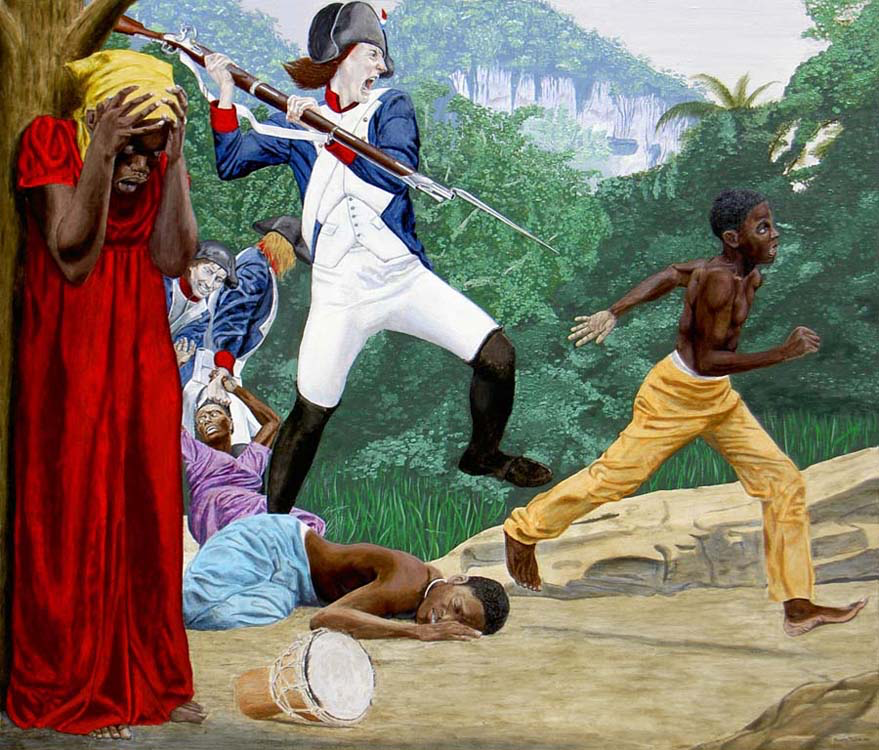

Kimathi Donkor, ‘CALL ME BLESSED’ 2016, oil and acrylic on canvas, 80 x 100 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Niru Ratnam Gallery.

I was motivated to create these idyll images when my wife was expecting our first child. To put it in context, many of my paintings are about disturbing, troubling and violent events. Even if they are not directly violent, you can sense threat and discomfort, evoking disturbing emotions. I had these paintings around my house, and I thought is this space comforting for a child? I wanted to create something more calming.

Also, creating scenes which are so volatile affects me because I am immersed in research about a particular historical period, or I am thinking about an experience I had in my life or may have witnessed, which can take it's toll. It doesn’t necessarily make you happy to create artwork about someone killed in a violent encounter with the police.

The idyll series is about the other side of life. Happiness, beauty, calm that one can encounter and from a very personal level through day-to-day experiences; I am very fortunate to have a lot of love in my life; I am surrounded by companionship, seeking out beautiful spaces to enjoy their company, and that is the vibe I wanted to share within the idyll series. Also, there is more realism for me with these series. The traumatic events and horrible things I've witnessed happen suddenly and can be brief. They might have long-lasting reverberations, and as artists, we tend to focus on these moments because of their political and social impact. However, the idyll series speaks to another set of moments, which can also be quite fleeting. Even in ordinary daily life, we're often filled with all kinds of pressures, worries and anxieties. Still, there are moments when you are in a park or your beach with your friends, and you think, Wow, this is nice; this is that moment when I can say, yeah, I love being alive. I just wanted to capture these moments in paint.

BT: The colour palette for 'On Episode Seven' and the works in the idyll series are exceptionally calming; can you tell me more about your process with choosing the colours?

KM: I think a lot about colour and the range of colours in a particular work; sometimes my palette can be limited and might be two or three colours, maybe black, white and brown. 'On Episode Seven' and the Idyl series has another range of colours, and I have thought a lot about colour intensity; I wanted the colours to be as intense as possible. You have pinks, purple, oranges, blues and greens, which are all exceptionally bright in the image. Although I don't do this systematically, when I am painting, I think about how I can get as many different colours in this as possible. It is like a rainbow, so a real vivid vicarious sense of life is coming through in the image.

These sets of works are also improvised. I don’t start with a plan or photographs and reference images; I have my paints, brushes and canvas. So regarding colour, it is not planned out, but I have some aims I am trying to achieve, such as how can I sit this colour next to another in a way that feels good? It is not a scientific exercise; it is about feelings.

BT: Do you use reference images for any of your artworks? Or are you constantly creating paintings from your mind?

KM: A lot of the work I produced in the 2000s was based on a mixture of imagination and memory, but I also used a lot of photographic references. I would do photoshoots with models with myself, go to locations, and seek out objects. . I would then edit and adjust the photos' compositions, play around with them in photoshop, and do collages and montages. However, I usually start my paintings with sketches, then move on to more defined drawings and use watercolours. , By then, I have a rough idea of the composition, such as where I wanted the subjects and objects to be and how I would picture the background. Then I started thinking about how to get a photographic representation that I could translate into the paint; it was a long-winded process. And although you get a very lifelike and realistic type of imagery, I got to the stage where I was becoming detached from the process; It did not feel creative, as too many steps were involved.

So I decided about a decade ago that I would stop working with this kind of reference and do what many painters do, especially those working in a more expressionistic mode which comes directly from the heart; I, too, wanted to blend my way of working and painting in a way that felt more natural to me and the process of being a painter.

For example, in the painting we are talking about, ‘On Episode Seven’, the sky, landscape, figures and their clothing look realistic, but this isn’t done by looking at a photographic image; I use my memory and imagination and decide how I want to convey an idea through paint rather than go through the lengthy process I was doing early on in my career.

Kimathi Donkor ‘On Episode Seven’ 2020, acrylic on linen, 64 x 79cm. Courtesy of the artist and Niru Ratnam Gallery.

BT: How have you developed your skills to master this way of working?

KM: Looking, I do a lot of looking. In the summer, I spend a lot of time with my family in the park, I have my sketchbook, but I don't bring it out all the time because that would kill the vibe, so I spend my time observing people and places I start to think how can I translate that into a painting. Looking intentionally has now become first nature rather than second nature. I hope that it gets stored in my mind and I use the knowledge I have gained from my time doing observational painting, portrait painting and watercolourist and then allow them to come together when I paint.

BT: Your doctoral thesis, 'Africana Unmasked,' reconsiders how art is interpreted in institutional and educational settings. I think this resonated with me, especially when I think about why I started Black Blossom, especially our school of art and culture; your research revealed how art had been dominated by perspectives emanating from a very narrow social basis - theorists and practitioners who were overwhelmingly male, middle-class, heterosexual and white. Why was it important for you to focus on in your art and academic practice?

KM: As an artist who works with various materials, I would say the first material you work with is yourself, where you've come from, where you have been, what you have been doing, what you've been looking at, what you're interested in. There are different ways you can frame that. I suppose I wanted to frame it in a sort of notion of diaspora and African identity. Because it's always been important to my life, I've travelled from one place to another; my family has been through various migratory diasporic experiences, whether through settlement, colonialism, or enslavement. They have been important shaping forces in my life, so my thesis proposed an artistic method of liberation from those oppressive histories by creating a progressive critique through painting.

BT: Thank you so much for this insightful interview. Where can people see more of your work?

KM: I have an exhibition opening at Niru Ratnam Gallery, where a selection of artwork from the Idyll series will be displayed alongside a new body of work that explores black subjectivity and identity, positioning the black subject back into the visual languages of art history. The show opens on 20 April and runs until 20 May.

The artwork ‘On Episode Seven’ will appear on the Holland Park Billboard throughout 2023; the song Kimathi chose for viewers to listen to whilst looking at the work is John Coltrane’s ‘Wise One.’