The Importance of Listening and Learning Across Generations: A Conversation with Sonia Boyce and Her Daughters, Maya and Aarony Bailey.

Acclaimed artist Sonia Boyce and her daughters, Maya Bailey and Aarony Bailey, share their thoughts on the transformative power of intergenerational dialogue in this enlightening discussion. From growing up in a household where creativity was celebrated to balancing motherhood and a successful career in the arts, the mother-daughter trio shares their candid insights and experiences. Discover how listening and learning across generations can help create a more inclusive and empowering art world in this thought-provoking exploration of the importance of passing the creative torch to future generations.

Sonia Boyce with her daughters, Maya Bailey (left) and Aarony Bailey (right). Location: Studio Voltaire’s Courtyard, 2023.

Bolanle Tajudeen: Thank you, Sonia, Maya and Aarony, for coming to my studio; I’m so sorry it is messy!! When I first had the idea to do this interview for the journal. I wanted to go all out and hire a stylist for a glamorous photoshoot.

Sonia Boyce: Bolanle, why glamorous?

Bolanle: It is such a special moment to have you alongside your daughters, who are already making major moves in the arts on Black Blossoms.

Sonia: It is more important to showcase the natural state of creating art rather than trying to create a glamorous image. The art-making process can be messy, and that's part of the process. I don't dress up in a ballgown in my studio; I am there working hard. I dress to work and create, not to impress anyone.

Bolanle: That's an excellent point, Sonia. How do you think this expectation of looking a particular way affects the work and creativity of women in the arts?

Sonia: This expectation of looking a certain way can undermine women's ability to explore their creativity freely and without constraints. It forces them to conform to a specific image and expectation rather than being true to themselves and their work.

Bolanle: Maya, can you relate to this expectation of looking presentable in the art world?

Maya Bailey : Absolutely, women are expected to look a certain way in the art world to be taken seriously, and unfortunately, this is not the case for men. I have to dress in a particular way and look presentable to get people to respect me, which can be frustrating.

Aarony Bailey: The art-making process is not always glamorous, contrary to the perception of it in the art world. It can be stressful, time-consuming, and quite draining. The art world tries to make it seem like it's all glamorous, especially for women. There's this idea of the troubled artist, and it's more acceptable for men to be gritty and edgy than for women. The focus on appearance in the art world takes away from the work of women artists. It's more important to focus on the work and the creativity rather than the appearance.

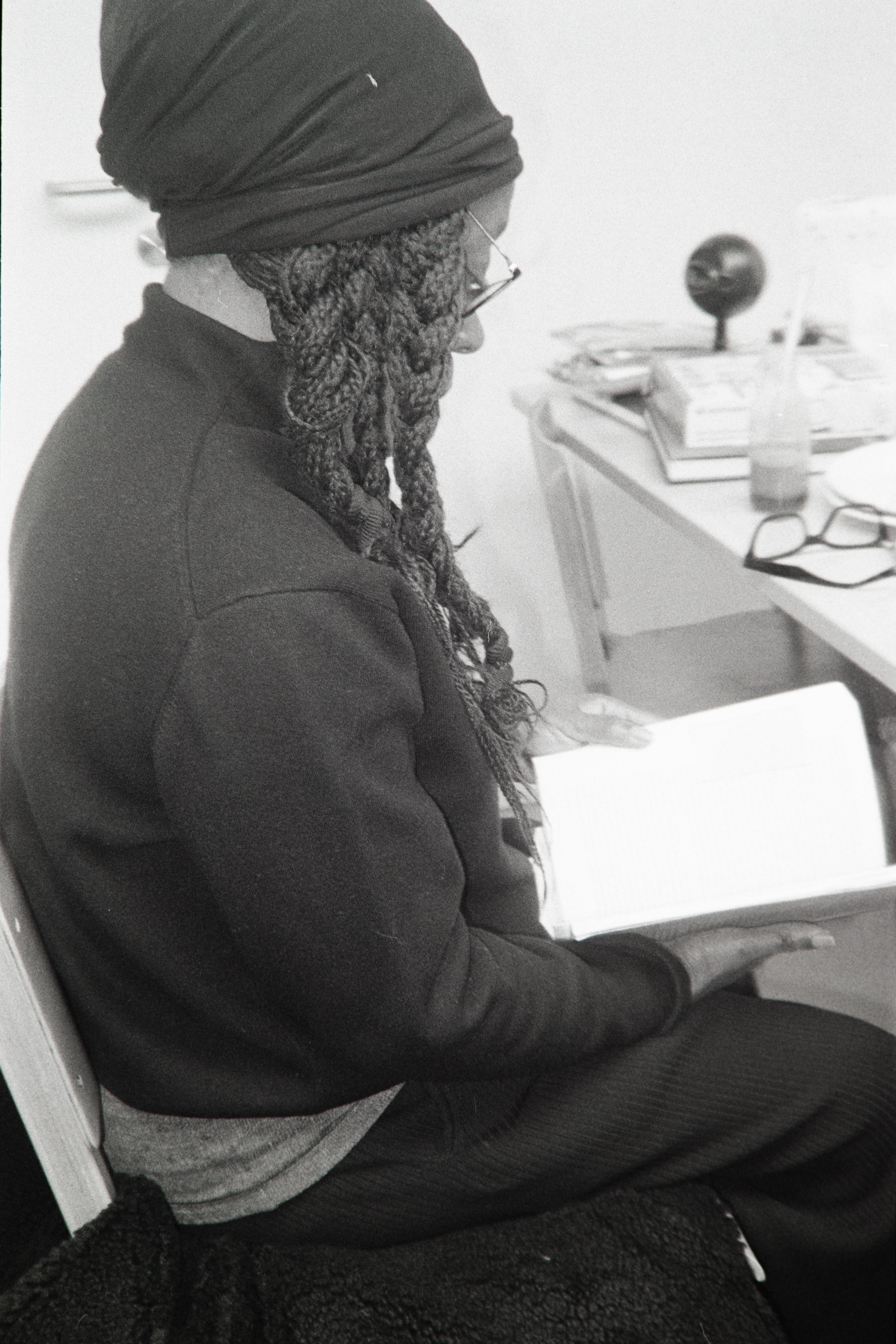

Sonia Boyce photographed by Aarony Bailey on 35m Film.

Bolanle : Sonia, what was your relationship like with your mother?

Sonia : My mother was a single parent with five children who worked two intense jobs as a nurse and a dressmaker doing piecework to provide for our family. Despite the challenges, she always found time to be a strong authority figure and support my decisions. When my art teacher recommended that I attend art school, she trusted the teacher's judgment, even though she didn't fully understand the art world.

Attending art school while doing office practice was challenging, but my mother recognised the value of a backup plan. She wanted me to have the security of a job while pursuing my creative passions. Her practicality and determination to provide for our family have stayed with me and continue to inspire me as an artist.

My mother's dressmaking skills were another significant influence on me. She used the cloth available at home from her piecework to create clothes for our family. This taught me the value of making something with your hands and sparked my creativity.

Meeting my grandmother in Barbados when I was 27 was a significant experience. She was a fish seller with a strong work ethic and determination to provide for her family. I come from a lineage of women who understood the meaning of working hard.

Bolanle: As a renowned artist and mother, have you balanced the demands of raising a family with pursuing a successful career in the arts?

Sonia: When I was pregnant with my first daughter, Maya, people often asked me if I would make art about motherhood. I found it strange that I was being asked this question as a woman but not the same question being asked of men. Being a mother is intimate for me, and nothing to do work about. For me, parenting was a shared role between their father, David and me, and he was very present and wanted to be. For example, he would take our children to meetings and galleries them on his back and front in a pouch; it wasn't easy balancing our career as artists with raising a family; we didn't have much money when the girls were younger to afford a childminder or housekeeper but we were fortunate enough to have the support of our extended family. Honestly, David and I really relied on our families to make it work. Parenting for me was a shared role, and David and I agreed on how to make it work. It wasn't easy, but it was possible with the help of our parents, grandparents, cousins, and siblings.

Bolanle: Aarony and Maya, you have not one artist but two artists' parents; what are some advantages and challenges of growing up in a creative household?

Aarony: Our house didn't look like other people's houses. It was chaotic, but that was just part of it. Our parents were always working on something, and our house reflected that. On a random Thursday, we would have to get ready for a private view because there was an exhibition opening, and I thought this was what all children did. Having artist’s parents gave me the confidence to do whatever i wanted and encouraged me to think in whatever way I wanted to believe. Maya and I were allowed to challenge the ideas and thoughts of people and be curious. I feel very privileged to have had that in my childhood. Anytime I did anything, my parents would always give a suggestion. They would ask questions like, "Why don't you do this?" or "Why don't you try to make a story with that?" They encouraged me to think beyond what I knew and to explore new possibilities.

. Aarony with her Mum Sonia inside Sola Olulode Studio at Studio Voltaire, 2023

Maya : One advantage of growing up in an artistic household is the ability to transition from lighthearted banter to deep artistic conversations seamlessly. It's hilarious and intense at the same time. We would have normal family jokes, make fun of my dad, and then suddenly talk about what it means to be a conceptual artist or, understandably, discuss cultural theory. And because I grew up around Stuart Hall and Paul Gilroy, my parent's friends, I was exposed to these types of conversations from a young age. I remember not knowing what my parents did and thinking they went to each other's houses and drank wine at dinner parties. Only when I started to go to college and university did I realise I knew the people they were talking about. When I first properly studied Stuart Hall, I had to call my mom and say, "What? What's going on?" I remember picking up a book about black artists and theorists and realising I knew 90% of the names in there. It wasn't new to me; it was part of my upbringing.

Bolanle: Maya, your bachelor’s degree is in Cultural Theory. How did growing up with your parents, Stuart Hall and Paul Gilroy, shape your undergraduate experience?

Maya: Most of the topics and theories explored were not new to me, as I had been exposed to cultural theory and discussions around black artists and creatives from a young age. My mother had contributed to a documentary with the BBC called 'Whoever Heard of a Black Artist', which explored artists of African and Asian descent who helped shape the history of British art. During my undergraduate studies, Whilst standing outside the lecture hall, someone questioned why it was necessary to have a documentary on this subject, to which I replied by asking, “Can you name five black artists?” I responded, “This is precisely why we all must watch this documentary.”

Bolanle: How does it feel for you, Sonia, knowing that your daughters are having similar conversations about the lack of representation and diversity in art?

Sonia: It's the lack of change and some changes over time. When I was studying in the late '70s and early '80s, I didn't know many black artists or artists of colour until I attended the First National Black Art Convention in 1981. I was shocked that I had been unaware of this and was further amazed when I attended the conference in '82 and saw over 200 artists of colour from all over the country. The lack of representation is due to an unconscious system of amnesia in art schools and the wider creative sphere, which is structural. The absence of people of colour in hiring or teaching roles and the lack of resources in libraries and programs all contribute to this. Although historically, people have been working to change this, the overall system emerges and disappears in a cycle. Thankfully, people are working institutionally to keep the memory legacy and to change the structure so that the legacy remains prominent.

In terms of changes, I have seen more initiatives and programs that aim to promote diversity in the art world. For example, almost ten years ago, a research project was done at the Slade about the presence of black people as models for the Bloomsbury group between 1913 and 1919. This is generations before The Carribean Artsist Movement, and it's essential to recognise these instances of research to create a timeline. The emerging generation must know that so they're not reinventing the wheel

Bolanle: Sonia, can you talk about the importance of recognising the contribution of people of colour in art history?

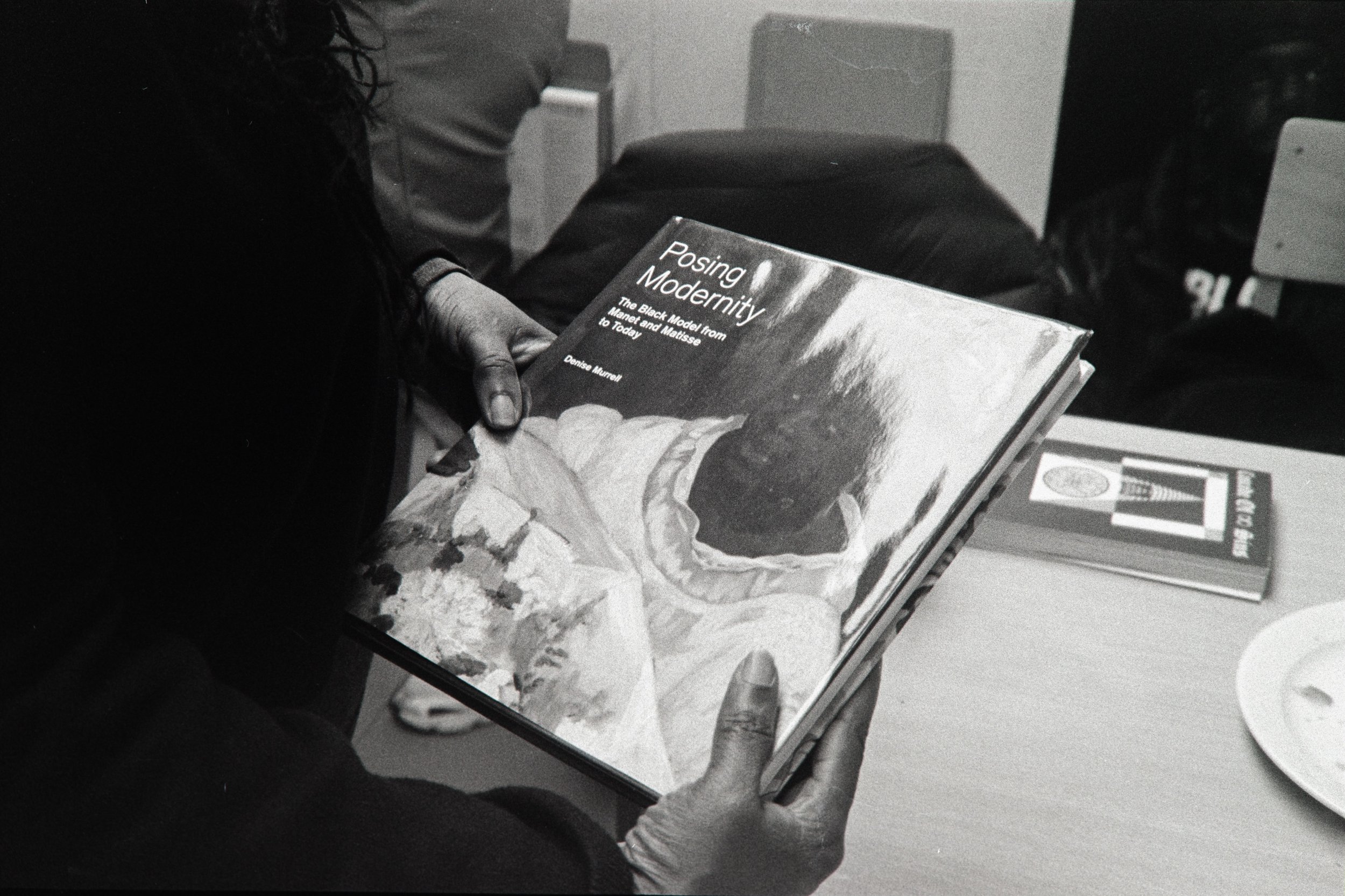

Sonia: Absolutely. Let me tell you about an exhibition my daughters and I saw in Paris in 2019. It was called ‘The Black Model: From Géricault to Matisse’ and curated by art historian Denise Murrell. The exhibition explored the role of the black model in art history and how black bodies have been represented throughout the history of art.

During the exhibition, we learned about Laura, a black model who worked for several prominent French painters in the 19th century. Denise Murrell extensively researched Laura's background, which uncovered a community of francophone Caribbean people living and working in Paris. Laura's story and the stories of other black models show the importance of recognising the contributions of people of colour in art history.

It's not just about the artists themselves but the people who inspired and influenced their work. We must bring the many untold stories like Laura's to light. By doing so, we can create a system where art by people of colour is just part of the public consciousness.

Bolanle: How has intergenerational dialogue and learning impacted your work as a filmmaker Aarony?

Aarony: Being exposed to different generations of the art world has expanded my understanding of the industry and its changes. Conversations with older artists have helped me appreciate the importance of diversity and inclusivity, influencing my work. For example, I am organising a film festival. I had three filmmakers in mind and realised all three were black women. This decision resulted from my exposure to different generations and my understanding the importance of diversity and inclusivity in the arts. Conversations with older artists and filmmakers who were open to understanding what younger artists are interested in and what we want to explore have influenced my vision for the festival. In this digital and environmentally conscious age, it is even more important to learn from those who came before us and to understand how our work can be more inclusive and sustainable.

Bolanle: How do you think intergenerational dialogue helps understand different perspectives in the art world?

Sonia: It's crucial to think intergenerationally because it requires listening, which can be challenging. We think we hear somebody but don't necessarily listen to them. We need to understand the character of each generation and what they are trying to achieve. But listening is vital, so we understand essential insights

Bolanle: Can you give an example of how we can miss important insights?

Sonia: Sure, a talk was given by Guy Brett at Tate about the work of Aubrey Williams. A post-war artist who studied in the UK but was originally from Guyana. His work was often abstract and semi-representational, and my generation had dismissed abstraction as indulgent and not dealing with the pertinent issues of the day. However, years later, at Brett's talk, he revealed that Williams' paintings were about the rainforest and ecology and were commenting on the destruction of the land in his native Guyana. Despite Williams' important message about environmental issues, my generation had missed it because we had assigned him to a particular place and not listened to where those connections might be. So as Aarony said, her generation is now working to be environmentally conscious.

Bolanle: That's a powerful example of what happens when we listen carefully. What do you think is the key to successful intergenerational dialogue and learning?

Sonia: The key is approaching it with an open mind and a willingness to learn and listen. Recognising that each generation has something unique to contribute and seeking out those contributions through meaningful conversations and interactions is essential. By doing so, we can gain a deeper understanding of the world around us and work towards creating a better future for all.

Bolanle: Maya, what does intergenerational dialogue mean to you in the context of Public relations and communication?

Maya: Inclusivity and dialogue between different generations in the art world are crucial. I first realised this when I met you at Frieze two years ago and shared with you that my mum was Sonia Boyce. You asked me what it was like to have a famous art mum, which is a question I often get from my peers in the arts. I remember an incident when you and I were walking around, I think, The Life Between Island show, and we bumped into Claudette Johnson, who we can agree is such a talented artist. Whilst in casual conversation, I remember noticing you becoming shy. At that moment, I realised how people often put artists on a pedestal. This further emphasises the need to bridge the gap between generations in the art world, that there is a need to facilitate more meaningful conversations and make the art world more accessible to everyone. That's why I decided to pursue a career in Public Relations focusing on Art Communication, to help create a more inclusive space for dialogue between emerging and established artists, critics, cultural theorists and art enthusiasts.

Bolanle: Lastly, Sonia, what advice have you given your daughters that we can all learn from?

Sonia: Regarding advice I've given my daughters, I remember conversing with them when they were around the same age but at different times. They would say, "Oh, other Mums can pick their kids up from school; why can’t you?" And I would get frustrated by this because I wanted both of my daughters to understand that they could have a life of their choosing, not just what was expected of them. If they wished for careers, they would have to work for them. And that might mean juggling the demands of working Mum and picking up the kids from school. But there are other ways to be a mom, and we shouldn't let society's pressures define us or our choices. We're constantly told what a good Mum or a good Dad should look like, and it's important to remember that there's no one right way to do it.

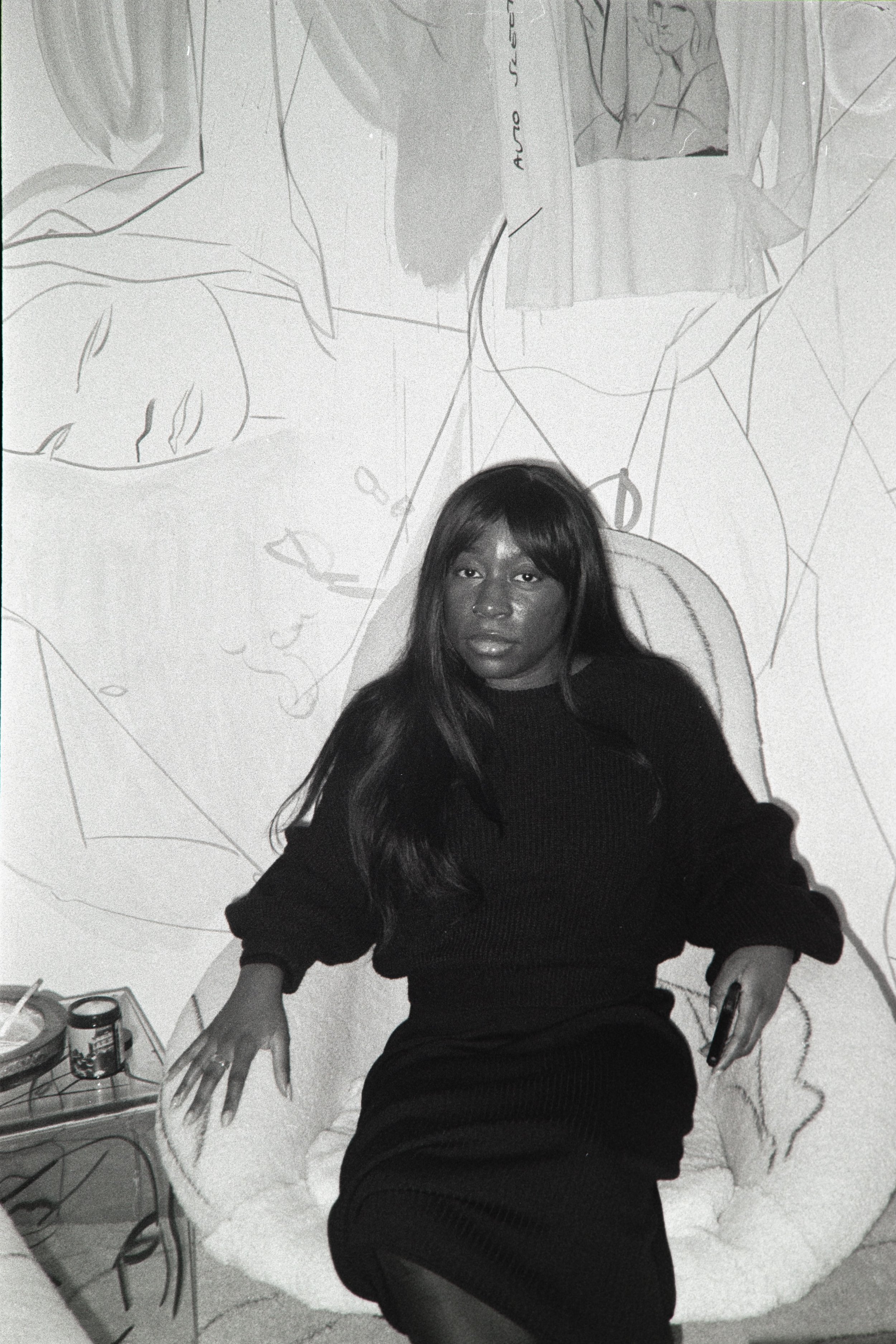

Sonia Boyce with her daughters, Maya Bailey (left) and Aarony Bailey (right). Location: Studio Voltaire’s Courtyard, 2023.