I want to explore their spiritual functionality, rather than just their aesthetic beauty.

Shannon Bono's first solo exhibition, 'The Hands That Hold You,' interrogates the spiritual function of African sculptures which depict Black women and reinforces the the power these objects hold in help her navigate society.

Shannon Bono in her studio at Anderson Contemporary Courtesy of Brynley Davies

“The overall aim of my work is to share everyday experiences of Black women with their personal experiences too.”

Approaching the balcony entrance of Anderson Contemporary a new gallery and studio space in East London supporting the areas creative community , I was greeted with the sound of R&B music and Afrobeats which complimented Shannon Bono artwork's celestial energy. Bono, who studied MA Art and Science at Central Saint Martins and is now a lecturer on the same programme, has demonstrated a unique ability to combine both disciplines in her exploration of the Black female figure in her practice.

The artworks in 'The Hands that Hold You' are ethereal aesthetically but deeply rooted and in conversation with Afrofemcentrism theory, made popular by well-known artists such as Faith Ringgold and Elizabeth Catlett. The work's structural integrity prompted connections to ideologies relating to the journeying between physical and non-physical spiritual planes.

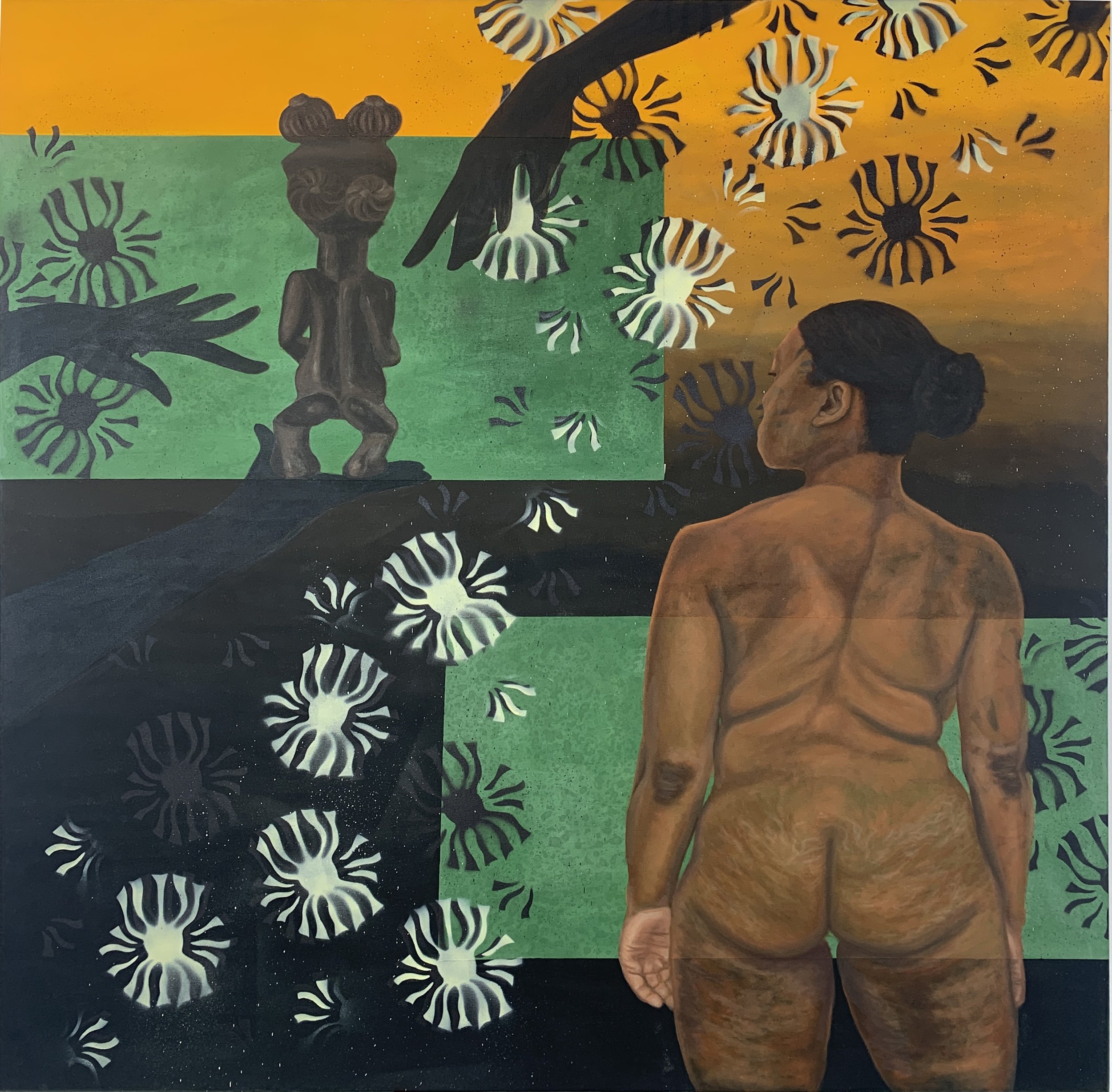

The paintings are rich and deeply considered, with an intense focus on inward-looking reflections of herself as the Black female figure that appeared in most of the works relating to her position as a Black woman in Western society. Figures are presented in dialogue and in conflict to display the spiritual power and functionalities of Black female-depicting artefacts and totems that are also present in the works.

Having seen Bono's work's in-group shows, her solo show gives viewers the chance to experience the artist's intentionality behind the artworks on a broader scale. Considering themes and explorations of the black female consciousness, spirituality and physical realities, I immediately had thoughts relating to magic and spirituality on first interactions with the work.

The introduction of this mysterious, shadowy black hand that appeared within multiple paintings in the show was intriguing and related to the titles, which suggest spiritual guidance, ancestral inquiry, self-preservation, and (re)discovery. Interacting with the work, I wanted to ask Bono how her visual language has developed during her residency at Anderson Contemporary, an artist studio and art gallery that focuses on nurturing and supporting artists. Although there was not much time to chat at the opening, we caught up a few days later over a zoom call.

Pacheanne Anderson: Your artwork has been included in notable exhibitions such as Bold Black & British at Christie's and Bloomberg New Contemporaries. What has the process been like to put on your first solo exhibition at Anderson Contemporary?

Shannon Bono: I have been in residency at Anderson Contemporary since February 2021, and I have had the privilege to be mentored by Micheala Yearwood Dan. She has a great understanding of my studio practice. Having a solo show was my goal from last year but was postponed because of the COVID restrictions. I am thrilled that I can do the show this year. All the artworks on display have been made during my residency.

PA: I enjoyed how different this body of work is; more suggestive, and you have moved away from bright colours encompassing more earthy tones. The signature biologically-infused and science-inspired backgrounds in conversation with the dutch wax fabrics that your audience is familiar with are present but have been scaled back and are less confrontational.

Could you tell me more about your process?

SB: For this series, I moved away from heavily patterned backgrounds. The works still have patterns and colours but are not full of colour like my earlier works. I used a lot of African artefacts within my practice, and I'm displaying their actual functional power. I wanted to transport the world that these figures were in and demonstrate the powers that we don't see, the things that are working that we don't see. The silhouetted hands represent ancestral guides and spirits that are with us.

Shannon Bono ‘ The hunters task in hand',’ 2021 Oil, acrylic and spray paint on canvas

“The hands might not necessarily be in view as they are metaphorically representative of energies working we can not see”

PA: The hands you are referring to are one of the first things I noticed when I looked at your works. What is the relationship between you, ancestral identities, and how the hand interacts with the African artefacts?

SB: The hands are not touching the figures; they are reaching out toward them or holding onto the actual sculptures. The hands represent spirit guides and ancestors working in our favour. Many of the poses and figures within the paintings are in this contemplative state where they are looking out and looking in, with a concern or worry about different things, including personal things that I put into the pieces. Often, the figures may be looking towards artefacts or sculptures. Still, the hands might not necessarily be in view as they are metaphorically representative of energies working we can not see.

PA: Each painting glows. There is an aesthetic and intellectual integrity that aims to present ancestral and non-tangible spiritual realms. Could you tell me about the importance of artefacts in relation to their functionality and true nature in the works?

SB: The artefacts present in work are from Congo. I wanted to have conversations about the nature of western archives and museums. Not only have they stolen precious artefacts from my father's country, but they mislabeled them, so there is a lot of misinformation about what the statues are for. I showed my dad an African artefact I was shown by a teacher, his response was 'Why are they showing you these artefacts, don't they know their purpose or power - these things can be dangerous?'. However, I believe in the westernised settings, the spiritual power of these objects have been removed.

The artworks on display in the exhibition feature influential feminine spiritual figures, Yombe and Luba. These Congolese female sculptures represent fertility and new life. It is believed Luba provides a vessel for the ancestors to reveal themself in the form of a child. The messaging behind the gestural quality of the figures featured in the works feel incredibly familiar. Through these new forms and structures, she represents and pays homage to those respected spiritual functions. Bono also refers to Nkisi - a non binary power figure, in the work Hunters Task in Hand.

PA: Portraiture is embedded throughout all of the artworks. The medium's integrity is further reinforced through the lack of a direct gaze or interaction with the onlooker. Your paintings reframe the nude black women figure (a self-portrait of you) away from the regular consumption of the Black female figure. I think this enriches the work's meaning and ability to assert agency and authority. Is that the intention?

SB: I focus on female-depicting artefacts. They are high ranking; they are spiritual guides. They are nurturers. I wanted to talk about those things in a contemporary western setting. My experiences of being a Black woman in this world and seeking help; I go to my ancestors, who help me navigate situations and the world. I want to explore their spiritual functionality, rather than just their aesthetic beauty."

PA: That's quite interesting; often, the figure depicted feels as if there is anxiety attached to it, evoking a sense of displacement or dislocation.

Is that a correct assumption to make here?

SB: I think in the beginning, when I was painting, I focused on the gaze; it was straightforward and engaging with the spectator to lock them in a position to experience the piece on show. It is a good thing you pointed out; they are in a state of reflection or contemplation - in a state of anxiety trying to figure things out. It's not directly looking at the audience. It's more so in a daydream or different world, which is why I changed the backgrounds in the works, bleeding into different colours, almost into a different realm - your physical body is here, but your mind is elsewhere. So I think what I was trying to convey with the pose of gesture and where the eyes are positioned.

Shannon Bono, ’Guardian of spirits,’ 2021 Oil, acrylic and spray paint on canvas

PA: What is your process like when starting new works?

SB: My art practice is research-led. It could be ethnographic research, going inwards, or reflecting about conversations that I have had with friends or stories that are important to share. For example, one of my works is about a friend. She is in a same-sex relationship and has discussed the process of having children in the UK, the difficulties of finding a black sperm donor, and just the process of family planning whilst queer. Until she shared her story with me, I didn't know any of it, so it was vital for me to share her story as it is beneficial for many other queer couples trying to start families. The overall aim of my work is to share everyday experiences of black women with their personal experiences too.