The Minimal Self: The Year I Arrived

Editor’s Note: On March 24th, 2023, Janine Francois presented her newly commissioned essay and staged a reading of 'Minimal Self' live at the Tate Late curated by Black Blossoms, in response to the theme of "Flourish." The work explored the intricate interplay between art and social justice, delving into the complex dynamics of identity, history, politics, and culture within the context of colonial and post-colonial migrations. Francois drew inspiration from Stuart Hall's 1987 essay 'Minimal Selves' and extended his argument to consider the notion of 'arrivals,' posing the question of whether one can ever truly 'arrive.'

The event provided a compelling platform for critical discourse and profound reflection, contributing to a deeper understanding of these vital issues. Notably, Hall's essay was written in the same year that Francois was born, adding a personal layer of connection to this work.

The theme of “Flourish” for the Late is particularly significant in relation to “The Unfinished Conversation,” a display curated by Aicha Mehrez paying tribute to the work of Stuart Hall. Hall is one of the most influential thinkers of our time, and his ideas on race, identity, and culture have shaped contemporary thinking in the field of cultural studies. We invite you to read Janine Francois' commissioned essay and reflect on the vital issues that it raises.

Janine Francois praying alongside the artwork by Emma Soyer ‘Two Children with a Book,’ 1831 at Tate Britain’s Tate Late curated by Black Blossoms. Photo by Tolu Elusade.

I was born in 1987 in Leytonstone, London, to a woman named Dee. Dee was born in 1958 in Castries, St. Lucia, to a woman named Marie. Marie was also born in Castries in 1919 to a woman named Enid. Enid, too, was born in Castries in 1902 to a woman named Philomena. Philomena was born in St. Lucia, location unknown, at some point in the 1890s. This is as far back as I know of my matrilineal line.

Tonight, my matrilineal line will serve as a metaphor for Black Feminist knowledge production within Tate Britain. How far back can we cite Black Feminist scholars? How many Black women artists are represented in Tate's collection? When do they appear? Let's consider collections as a form of memorialisation: which artists are privileged enough to be immortalised, and which ones are not? How is collecting a political act of remembrance and visibility?

Rebecca Bellantoni (sound by Rowdy SS) ‘Condition the roses, accept the vision. C.R.Y.’ (Installation View and Performance) At Tate Britain’s Tate Late curated by Black Blossoms.

Photos: Courtesy Tate/Eugenio Falcioni.

In her groundbreaking text, "Black Feminist Thought," Patricia Hill Collins reminds us that "Black Women have had to struggle against white male interpretations of the world" (2000, p. 268). bell hooks writes in "Salvation: Black People and Love" that "White supremacist, capitalist, patriarchal leaders know who benefits from the disrespect and devaluation of black female wisdom" (2001, p. 223). Collins, hooks, and I, along with many others, must contend with how white supremacist, colonial patriarchy has excluded and attempted to deny Black Women as knowledge holders and makers, as well as artists.

Workshops and activations led by Stafi Samaki, Black Girl Knit Club, Jahnavi Innis at Tate Britain's Tate Late curated by Black Blossoms. Photos Courtesy Tate/Eugenio Falcioni.

Returning to the metaphor of my foremothers, while my knowledge of their existence may end at a particular point, this does not mean an end to that knowledge. Why? Because knowledge is embodied. Embodied knowledge refers to knowledges that are learned and absorbed into our physical and metaphysical bodies, as well as our emotions, providing unique ways of knowing and existing in the world. Black Feminist knowledge, through its complex, experiential, and cerebral ways of existing, seeks to disrupt and reject Eurocentric philosophies that attempt to separate the mind, the body, and the spirit. I perceive Black Feminist knowledge to be nuanced, complex processes that are ever-expanding and intersecting across time, place, and bodies.

Art museums would deeply benefit from Black Feminism. However, they are places where invisible forms of dominance reside, and they mediate historical and contemporary social relations. Tate Britain's artwork, wall text, and institutional narrative implicate Britain's involvement within the colonial project, and yet we are expected to coexist with them despite the harm they cause.

Take my body, for instance. I carry the traumas of the middle passage, chattel slavery, colonisation, and migration. However, I am also a survivor of these traumas that run deep inside me. These traumas are embodied memories and resistances that bond mine and a multitude of other Black bodies across the personal, the collective, and the historical. This proves that Black bodies complicate linear time because we reveal its racism and gross fabrications. Western mechanical clock time excludes Black bodies from Britishness and positions us as outside of modernity, and yet we are still here dealing with the legacies of slavery and colonisation. The linear timeframe employed within Tate Britain first recognises a Black male artist in the 1930s and a Black woman in the 1980s. Using this institutional narrative alone, we would assume this was when Black men and Black women began to make art.

Elsa James ‘How can we flourish?’ (Performance) At Tate Britain Tate Late curated by Black Blossoms. Photo: Courtesy Tate/Eugenio Falcioni.

However, art museums were designed to privilege white bodies and exclude Black ones, except when it is time to clean up after them or enact border control upon who can or cannot walk through their doors. This is not a criticism of such labour; these workers are grossly underpaid and undervalued, yet they intimately know the contours of these buildings. They clean the crumbs from our desks, knowing what we ate that day, and when they search our bags, they discover the secrets they hold.

If we think of the Black girls depicted behind me as representations of real people and if we interweave their bodies alongside mine, we experience the past and present as colliding and competing temporalities; put more, these two girls are not 'dead'; they are living through my body.

Our historical entanglements complicate Britishness. At what point between our shared histories and realities do we get to claim 'Britishness?' It is an important question to pose, given the ephemerality of British citizenship if you are non-white. Does my 'Britishness' begin with my birth, that of my parents, or when my grandparents migrated to this country as former colonial subjects? And what about theirs? Are they British because they live in Tate Britain, were painted by a white female British artist, may have been the 'property' of a British plantation owner, or because, at one point, alongside many others, one-quarter of the globe belonged to the British Empire? This is why notions of Britishness must always be contested, even in a space like Tate Britain. However, conceptualising a global diasporic Blackness as transcending African peoples' shared history of colonialism, resistance, and spiritualities is my preferred point of arrival. I believe Black Blossom's takeover embodies this energy tonight in this place we call 'Tate Britain.'

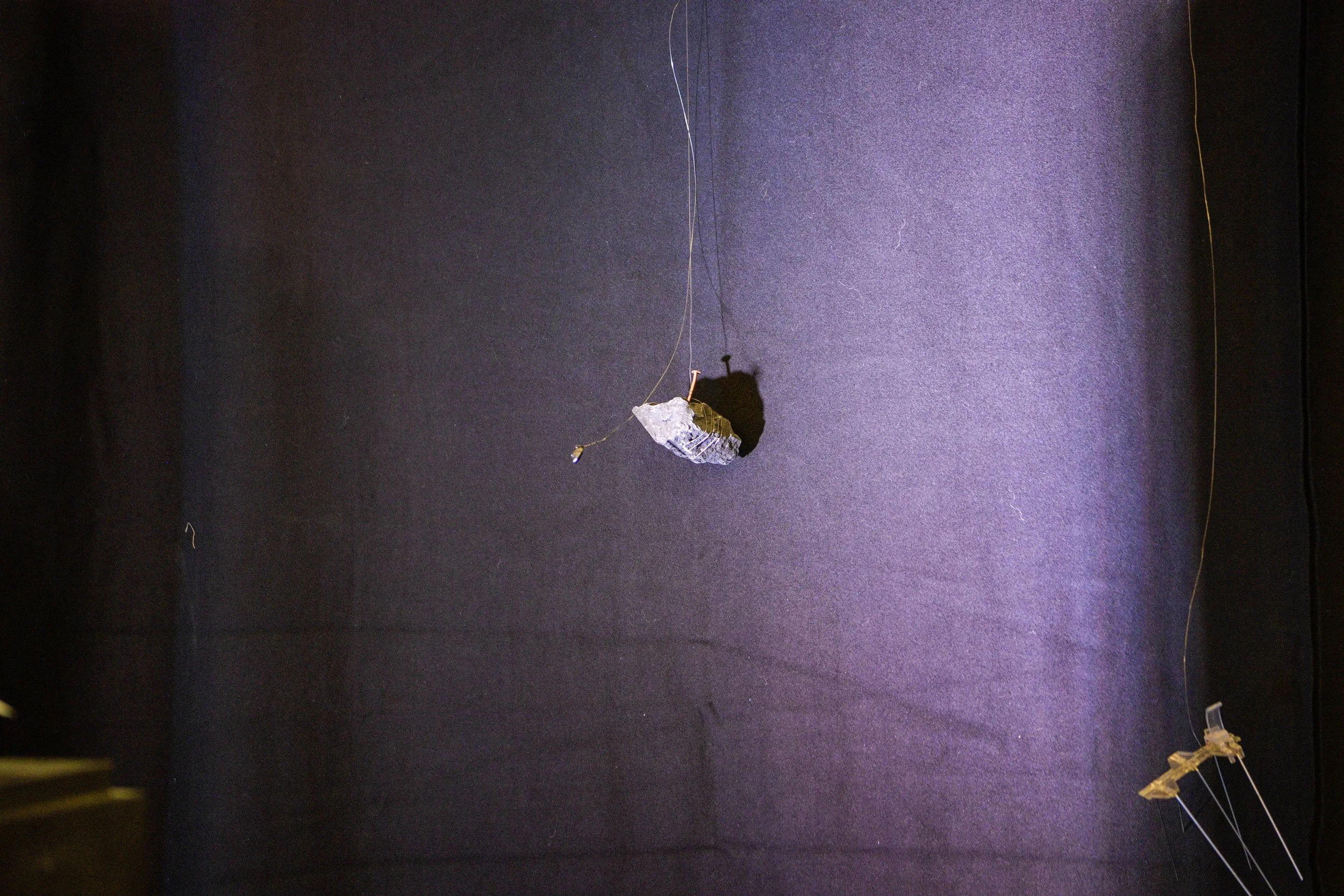

Hamed Maiye ‘Libations for those in limbo’ a collaboration with Rotimi Skyers and Zachary Cayenne-Elliot’ (Installation View) At Tate Britain’s Tate Late curated by Black Blossoms.

Photos: Courtesy Tate/Eugenio Falcioni.

I want to turn our attention to Bolanle Tajudeen, the Founder and Director of Black Blossoms, who has curated a constellation of artistic practices, conversations, and interventions, all of which are provocations to re-centre Black bodies that have long been denied, erased, neglected, and most often forgotten. Well, not by all of us. Tonight, in alphabetical order of first names, we have the contributions of; Black Girl Knit Club, Devaughan John, Elsa James, Ezri Francis, Hamed Maiye, Husna Memon, Jahnavi Innis, me - Janine Francois, Lisa Anderson, Rebecca Bellantoni, Rotimi Skyers, Rowdy SS, Stafi Samaki, Symeon Brown, Tolu Elusade, Tolu House of Revlon, and Zach Cayenne-Elliott, with special thanks to Ese Jade Onojeruo, Tram Nguyen, the Tate Collective, and Public Programmes.

The Black Blossom takeover is far from a 'moment'; it is the next chapter in a very long history of Black artists, curators, and academics who have, in their own unique ways, challenged and fought back against these paradigms while creating their own artistic spaces.

We have all arrived in this place, with its contested history, a history that also forms part of our individual and collective biographies. Nonetheless, it is a history still incomplete, as we are all still yet to live it.

Symeon Brown and Lisa Anderson in conversation at Tate Britain's Tate Late curated by Black Blossoms. Photos: Courtesy Tate/Eugenio Falcioni.

Tonight, we will all be written into the archives and the art books, imprinted into our memories that will live through our descendants, who will one day look back at this moment alongside an archipelago of others and thank us for shifting British consciousness.

It has been my honour to open tonight's gathering and welcome you and the individuals named who have contributed to this takeover in myriad ways.

I would like to end with a quote from one of my favourite philosophers, Jay Z, "Thanks for coming out tonight, you could have been anywhere in the world, but you are here with [us], and [we] appreciate that

Thank you.